COP26 has ended, and, as most in the climate community expected, the conference signaled a series of incremental, positive steps at a time when the science backs bigger commitments and more decisive action.

As one government source who was in Glasgow told us, “we really need some tech breakthroughs at commercial scale in the next five years to get us through [and keep us on the path to 1.5 C]. The private sector was very active, more than ever before, but governments aren’t doing enough, so it’s on the public to keep pushing. Hopefully both companies and governments respond to that.”

One of the central themes in Glasgow — and one of the primary reasons international climate compromise continues to be so difficult — was global climate equity. In other words, what should “fair” international climate collaboration look like? And why is equity an important lens on climate action?

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley speaking at COP26

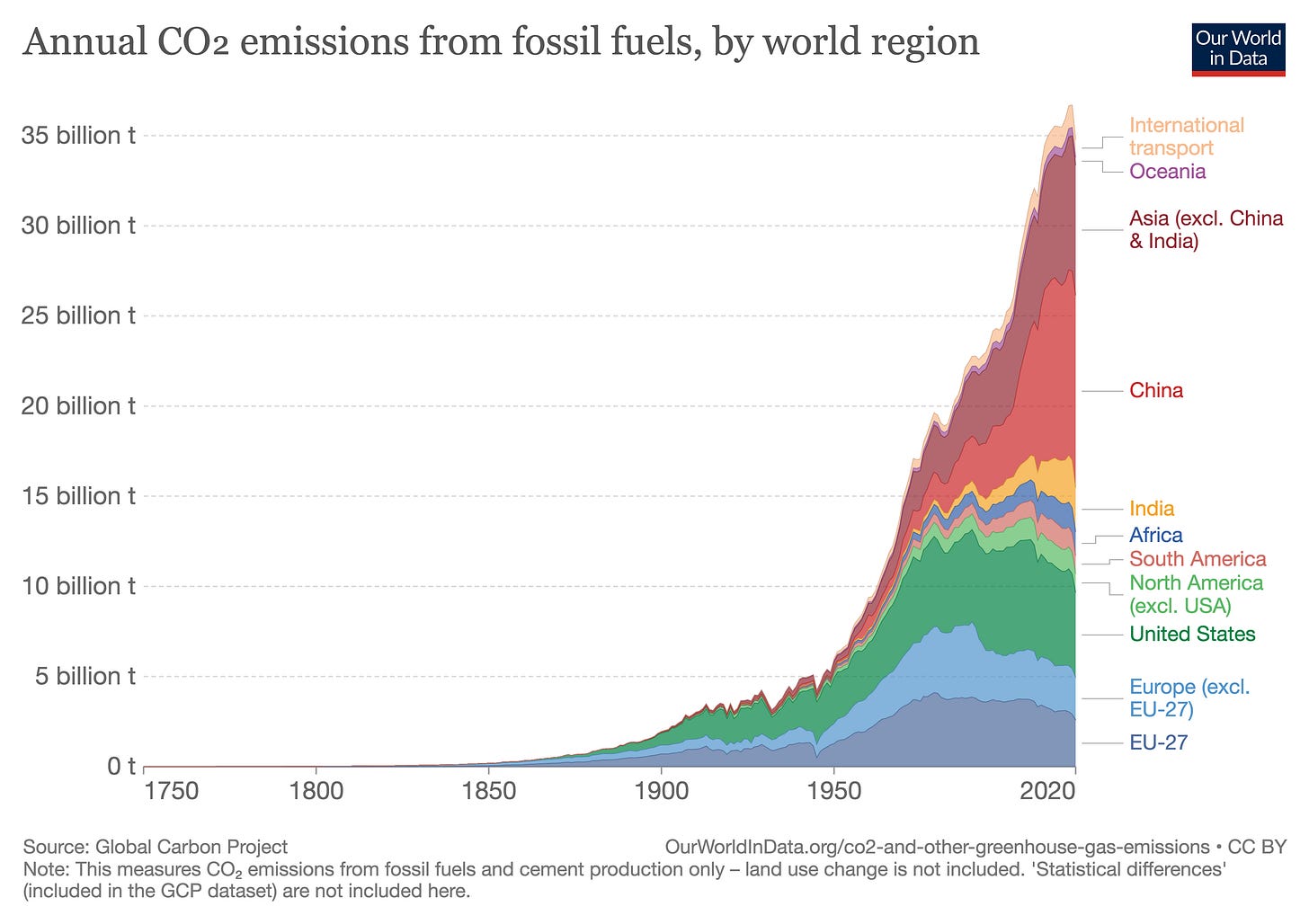

If we take a step back in history, human economic growth and wealth creation over the last two hundred years is quite remarkable. We profoundly changed the world we live in, in so many different ways.

What bent the curve so dramatically? If you had to pick one event as a historian, a safe choice is James Watt’s 1764 steam engine design. By venting spent steam out of the engine (what we might call an exhaust today), Watt’s design dramatically increased the amount of work an engine could generate per unit of fuel consumed.

This design — and further improvements and innovations on top of it — gave us the industrial revolution, trains, cars, planes, and combustion engines — powered by fossil fuels.

Countries and regions that industrialized the earliest and most aggressively, like the United States and Europe, achieved dramatic improvements in wealth, prosperity, and economic growth.

And, if you look at a map like this, you can also see immense wealth accruing to countries like Saudi Arabia (the world’s largest oil exporter), Australia (one of the world’s leading coal exporters), and Norway (Western Europe’s largest oil and gas producer) — the raw material providers who powered our modern economic era.

The problem — from both a science and international relations standpoint — is this trend isn’t sustainable for the Earth. We need this economic era to end to avoid catastophic future climate change.

But if you’re not a wealthy country today, that’s highly problematic in several ways.

First, as we’ve detailed before, the Global South and equator regions — Africa, Central America, South America — are parts of the world hit hardest by climate. So it’s not unfounded to say that the Global North got rich industrializing off fossil fuels, then passed the consequences and fallout south. Not exactly fair.

Second, while it’s true we didn’t understand climate science very well when we were building iron works and textile plants across New England and Northern Europe in the 18th century, there’s a layer of intrinsic hypocracy for rich, industrialized countries to turn to poorer countries and say “we got to industrialize and improve our standard of living because we did it early, but things have changed so now you can’t.”

While it’s true China — the world’s largest emissions polluter today — industrialized more recently [in a sense globalization merely shifted manufacturing emissions from Western high-consumption economies like the US over to China], overall wealthy nations represent the bulk of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The top 1% of wealth around the world produces 15% of global GHG, twice as much as the bottom 50%, whose total emissions are just 7% of the total. The global rich fuel the climate crisis.

So what does global climate equity look like in 2021?

Paying for the Consequences

The first major (and contentious) theme in the climate equity conversation is who pays for the damage. There have been efforts in both the developed and developing world to hold major fossil fuel polluters like Saudi Aramco, Exxon Mobil, and Royal Dutch Shell financially accountable for their role fueling the climate crisis. Barring that, many vulnerable countries at the front lines of climate change are looking for broader economic development help from wealthy nations to adapt and support local climate resilience efforts.

Maldives, for example, a nation of 1,138 low sea-level islands southwest of India, now spends 30% of its annual government budget adapting to climate change to deal with flooding, water desalinization, plastic pollution, and other environmental damage.

At COP26 a headline demand from emerging economies was for rich countries to accelerate and deliver on a promised $100 billion dollars in climate finance aid to poorer countries. In coming years, this sum will need more zeros. India alone estimates it needs $1 trillion by 2030 to fund its decarbonization efforts and expand clean energy capacity.

As attendee Mohamed Adow from Power Shift Africa noted, “The outcome here [at COP26] reflects a COP held in the rich world and the outcome contains the priorities of the rich world. Not only did developed countries fail to deliver the long promised $100 billion of climate finance to poorer countries, they have also failed to recognise the urgency of delivering this financial support and setting a clear process for it.”

Planning for Population Shifts

At our current rate of global GHG emissions, by 2070, scientists suggest nearly 3 billion people will have to get by — or relocate, if possible — against “unlivable” weather conditions. Unless we divert course, we are approaching a historic global period for climate refugees.

The question then becomes, will the Global North accept them? At COP26 South Sudanese diplomat Lumumba Di-Aping made the request loud and clear: “The first resolution that should be agreed in Glasgow is for annex I polluters to grant the citizens of small island developing states the right to immigration.”

But will the countries who created this disaster accept the vulnerable? And on what scale? No clear policies, frameworks, or agreements emerged from COP26, and in many countries far-right and nationalist politicians continue to demonize immigration.

Walking the Talk

The other side of the equation is decarbonization by wealthy, industrial nations. Funding climate adaption economic development in frontline countries doesn’t do much good if major economies continue to cancel the positive by emitting more GHG.

Here in particular, COP26 failed to deliver on its potential. In his closing statement, UN Secretary-General António Guterres was particularly candid: “We did not achieve these goals at this conference. But we have some building blocks for progress. I know you are disappointed. But the path of progress is not always a straight line. Sometimes there are detours. Sometimes there are ditches. But I know we can get there. We are in the fight of our lives, and this fight must be won. Never give up. Never retreat. Keep pushing forward.”

Here in the US, hopefully we can. This morning the House of Representatives finally passed the Build Back Better (BBB) Act, which includes $555 billion for fighting climate change. The main climate provision in the bill offers $320 billion in tax credits to incentivize and reduce the cost for companies and households to install solar panels, improve the energy efficiency of buildings and homes, and purchase electric vehicles. The bill also provides incentives for domestic cleantech manufacturing, and would help fund a Civilian Climate Corps with the goal of creating 300,000 jobs to restore national parks, forests, and wetlands —similar to the New Deal-era Civilian Conservation Corps.

It remains to be seen if BBB can survive the Senate fully intact.

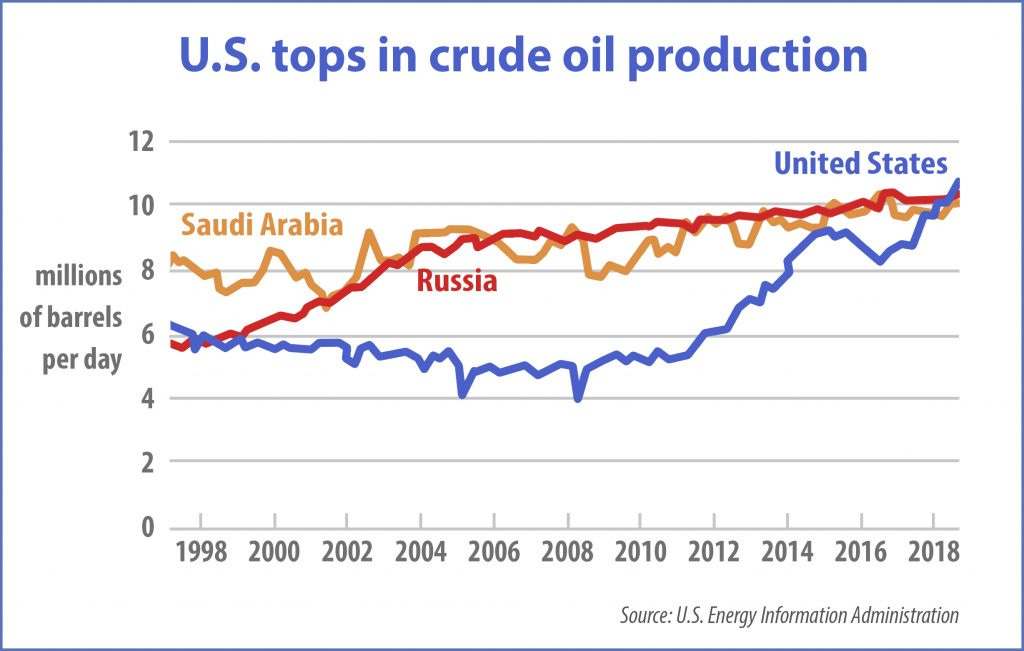

And BBB or not, there’s still plenty more work to do. For example, is there any sensible reason the United States should be the world’s leading oil producer in 2021 with all the writing currently on the wall? This is yet another place where the trend is headed in entirely the wrong way.

As the climate crisis progresses, global climate equity will continue to be an important part of the conversation. And, while we’re here, let’s not forget vaccine equity either.

—

This Week in Sustainability is a weekly(ish) email from Brightest (and friends) about sustainability and climate strategy. If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider forwarding it to a friend or teammate. If you’re reading for the first time, we hope you enjoyed it enough to consider subscribing. If we can be helpful to you or your organization’s sustainability, ESG, or social impact journey, please be in touch.